Please see below key updates provided by network members. Note: Service disruptions for all will depend on the severity of…

The Guardian Opinion article by Maggie Shambrook – a founding participant of the Housing Older Women Movement. For many older…

City of Moreton Bay CEO says change that will see homeless face threat of fines is needed for health and…

New analysis from the Foyer Foundation has identified the 20 toughest places across the country for young people to find…

First home buyers purchasing a new build will no longer need to pay stamp duty under new laws set to…

‘Decades of poor performance’ in dwelling construction is contributing to the housing affordability crisis, report says. The Australian housing construction…

- Queensland Statewide (all regions)

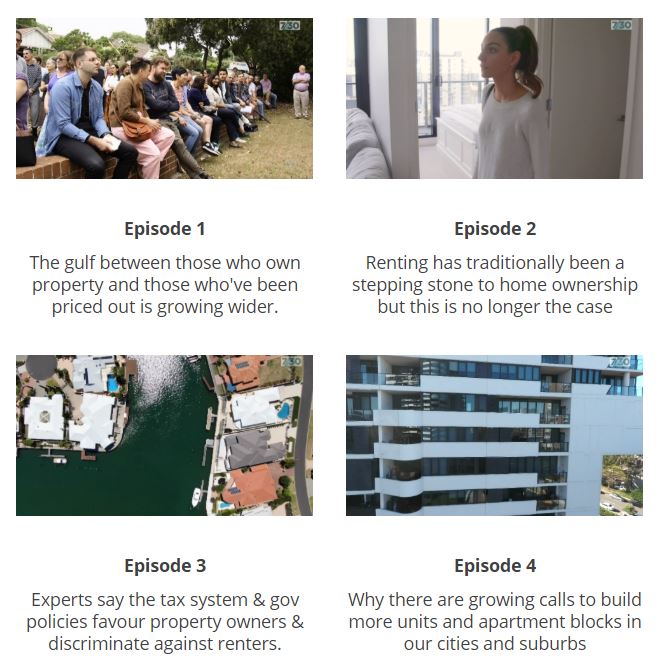

ABC 7.30 screened a four-part housing special examining a number of housing related issues from Australia’s housing markets to housing…

- Queensland Statewide (all regions)

The problems of housing crises, gentrification, homelessness, unfettered real estate capital and unregulated development are hardly unfamiliar issues. Their effects…

- Queensland Statewide (all regions)

After testing the market with a small-scale affordable housing development in Sydney, property advisory group Development Finance Partners (DFP) is…

- Queensland Statewide (all regions)

While discussions about the accuracy of the latest government figures for numbers of rough sleepers in England and Wales will…

- Queensland Statewide (all regions)

How would you feel if — homeless and at your lowest ebb — the room you’re offered is bare, its…

- Queensland Statewide (all regions)

On the fringes and often unheard, those who have experienced homelessness are rarely given a voice. When more than 100…

- Queensland Statewide (all regions)

Afew weeks ago in Auckland, while getting into a cab, a colleague and I were having an animated discussion about…

- Queensland Statewide (all regions)

Rough sleepers are sheltering in bins all year round, with surging homelessness in the UK blamed for a rising number…